You’re Not Losing. You’re Being Harvested

Capitalism isn’t broken. It’s evolving into something else, working exactly as designed, and you’re the yield.

I’ve written a lot about economics—how we got here, how capitalism works (or doesn’t), and what happens when you unshackle money from gold, labor, or even logic. I’ve written about Modern Monetary Theory, High-Powered Money, and the strange magic of fiat currency.

But I’ll be honest: COVID clarified something no textbook ever did.

It taught me that access to capital matters more than profitability.

And access to power matters more than both.

During COVID, I watched profitable businesses collapse—restaurants, dry cleaners, pizzerias. Some of the best in the world folded not because their model was broken, but because when the economy hit pause, they couldn’t access the two things that matter in a post-capitalist system: capital and influence.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk—an emerald mine heir turned algorithmic thief LARPing as a modern-day coal baron—bought Twitter for fun and used his wealth not to produce value but to reshape narratives, markets, and political discourse.

At a certain level, money stops buying things.

It starts buying leverage.

That’s the fundamental shift.

After a certain threshold—somewhere around $100 million, maybe $500 million—the utility of more money stops being about consumption. You can already finance the jet, the skyscraper, the football team. What more money gets you now isn’t stuff. It’s insulation. It’s access. It’s power.

So when people ask, “Why do billionaires still chase more?”—this article is the answer.

Because we’re not in capitalism anymore.

We’re in something else.

The Lie You Still Believe

We were all sold the same story:

Work hard. Earn money. Spend less than you make. Invest the rest. Retire comfortably.

That was capitalism—at least the mythic version: moral, meritocratic, and mathematically sound.

And for a while, it worked. Roughly from 1945 to 1975, productivity gains translated into real wage growth. A single income could support a household. Corporations paid taxes. CEOs earned 20–30x what their average worker made. And while inequality still existed, the upward escalator generally moved in sync with effort and output.

I’ve written about this at some length.

But somewhere around the year 2000, the engine began to sputter.

The dot-com crash didn't just pop a bubble—it exposed a more profound truth: profits no longer mattered. Companies that had never turned a dollar of earnings were trading at multi-billion-dollar valuations. The logic of capital had started to untether from the cash flow logic.

Now, at the time, the idea of irrationality that led to gigantic mistakes was thought to be the cause and effect. Everyone just got way too excited about douchebags with fooz-ball tables, smoking weed, drinking green juice, and writing code.

But as I’ve come to look back, that’s not what happened. A ton of people got really rich during the “dot-com” era. It demonstrated that the rules had changed. So, in the next evolution, the focus wasn’t just on the “sizzle,” but just an ever so slightly more emphasis on the steak.

What comes out of this period? Amazon. eBay. NVIDIA. Google. You begin to see the beginning of the end of newspapers, television news, and what would become known as the “democratization of the creative” (namely, the ability to create content.) Software companies drive this phenomenon. What used to take professional artists weeks can now be done by a geek who learns software in a day. It radically transforms everything.

What emerges out of all of this? A new class of elites that would become billionaires—not builders of machines, but builders of monopolies:

Jeff Bezos turned bookselling into an empire by losing money for over a decade while capturing the infrastructure of commerce.

Elon Musk sold vision, volatility, and vertical integration—and was rewarded handsomely for it in multiple ventures. He never invented a thing, just figured out how to sell it and kill every competitor around him.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin replaced every card catalogue at every library in the world with simple searching online.

Mark Zuckerberg didn't sell anything at all. He sold you—your data, your preferences, your behavior.

They weren’t just wealthy. They were systemically immune to the constraints of traditional economics. The rules didn’t apply to them because they owned the platforms that rewrote the rules.

In “Barbarians at the Gate,” James Garner portrays F. Ross Johnson, the man who would lead an unsuccessful bid for RJR-NABISCO in the 1980s. The movie is based on the book written by John Helyar and Bryan Burrough. In it, Johnson explains to H. John Greeniaus (played by Jeffrey DeMunn; Greeniaus was the head of the food division of NABISCO) said that if he went along with him (Ross), he wouldn’t just get rich. He’d have “Not just, ’Fuck You money.’ We’re talking, ’Fuck EVERYBODY money.’”

In retrospect, the craziness of the 1980s and the mergers were perhaps the sparks that would later combine with the “rise of the monopolists” roughly twenty years later.

That’s what people like Musk, Page, Zuckerberg, developed. They indeed became as wealthy as Nations. They developed “Fuck everybody money.”

And in this era, being profitable became a liability.

Why? Profits attract taxes, force discipline, and imply maturity, which Wall Street interprets as stagnation. So companies learned to burn cash strategically—to juice growth, eliminate competition, and keep the valuation game alive.

Sometimes, the process gets out of control: WorldComm. Enron. GM. And of course, the granddaddy of fuckups-Lehman.

But somewhere around the 2000s, the system started whispering its secret:

“You don’t need to make money if you can convince people you might someday.”

That whisper became a chorus. And that chorus became gospel.

Can I get an “Amen!” brothers and sisters! Hallejua! Praise the shell game.1

From Capital to Chokepoints

Capitalism used to be about production: Make something. Sell it. Reinvest. Grow.

Back in the day, efficiency mattered. Companies competed by getting better at what they did—cheaper, faster, more reliable. Build a better mousetrap and get better at making, marketing, and distributing it, and you’d win. Entire empires were built on operational excellence.

That was capitalism: risk, production, profit.

But now?

Now, the winners don’t make things.

They own bottlenecks.

They don’t build mousetraps. They build tollbooths.

Amazon doesn’t make most of what it sells. It rents the infrastructure and takes a cut from every merchant who passes through.

Uber doesn’t own the cars. It owns the dispatch logic—the algorithmic gatekeeper that skims every ride.

Spotify doesn’t produce music. It builds the gate between the artist and the listener, and quietly taxes the exchange.

Substack doesn’t produce content. It built the framework to facilitate subscription transactions and takes 10% off the top.

This isn’t innovation. It’s intermediation. This isn’t entrepreneurship. It’s enclosure. What we’re living in now is rentier capitalism—a system in which real money isn’t made by producing value but by controlling access to it.2

And it shows up in your everyday life.

In 2019, $500 could buy you a decent mid-range smartphone, outright. You paid once, you owned it. No strings attached.

In 2025? That same $500 might cover three or four installment payments on a device you’ll never technically own—one where half the features are locked behind software subscriptions, and replacing the battery requires a $200 service appointment and permission from the manufacturer.

The product hasn’t changed. But the ownership model has.

Meanwhile, over that same period, a $100,000 investment in the stock market quietly became $130,000—with no labor, no effort, no production. Entirely passive.

The investor is rewarded for holding.

The consumer is penalized for needing.

And the producer? Left behind. Almost entirely.

(Which, not coincidentally, is what gives rise to someone like Donald Trump—promising to reopen the factory, revive the town, and bring back a dream that’s been dead for decades. It’s a pipe dream. But when the economy offers you nothing else, belief becomes the only rational option.)

Between 2000 and 2020, the U.S. lost nearly 6 million manufacturing jobs. This was not because we stopped needing goods, but because finance and chokepoint platforms outperformed production.3

Why spend decades building machines when you can build a marketplace and skim a fee off someone else’s labor?

This is why the steel mill shut down. This is why industrial towns hollowed out. It wasn’t just globalization or trade deals. It was profit-motive economics.

You had two choices:

Spend $1 million in capital, build a factory, innovate, scale, hire, and maybe—maybe—make a $300K profit over a year.

Or spend the same $1 million on the right pre-IPO deal, the right SaaS platform, the right token... and make $200 million in six minutes.

Which one do you think most people chose? (Hint: it’s why nobody makes doodly.)

That’s why manufacturing left.

Manufacturing used to be the backbone of middle-class wealth. It created stable jobs, regional economies, and national trade surpluses. But in today’s system, factories are liabilities—high overhead, regulatory burdens, hard to offshore fast enough.

And for those who want to blame the EPA or ANWR or chemical dumping regulations: Stop. It wasn’t environmental policy. It was economics.

The market didn’t reward the manufacturer; it rewarded the middleman, and the market is all that matters.

That’s not just inflation. That’s engineered extraction—a system designed to skim, not serve.

Because if you produce something, you can make a living. Maybe.

But if you own the gate?

You can build an empire.

Who Gets Rich Making Things? (Nobody.)

Are any billionaires today people who got rich by building factories?

Not outsourcing. Not licensing. Not flipping real estate or trading derivatives.

I mean building something—machines, physical goods, with workers, in a plant.

The answer?

Almost none.

In today’s economy, building physical things is considered quaint. A hobby. A liability. The real money is in controlling distribution, IP, and platform access. The few examples that seem like exceptions? They unravel fast.

Take Elon Musk. He didn’t found Tesla—he bought in early. Tesla’s value isn’t in selling cars. It’s in controlling the narrative, extracting subsidies, and leveraging hype into valuations. Tesla is a financial instrument disguised as an automaker. The car is just the delivery vehicle for the stock price.

What about James Dyson? Yes, he built a real product company. Vacuums, dryers, bladeless fans. But even Dyson eventually offshored most of his manufacturing to Malaysia.

In the U.S.? It’s basically a graveyard. There is no American billionaire today who built their fortune from scratch and built it on domestic manufacturing at scale.

Not one.

Most modern billionaires came up through:

Tech platforms (Zuckerberg, Page, Bezos)

Finance (Dalio, Griffin, Thiel)

Real estate and franchising

Licensing, subscriptions, and IP extraction

Or inheritance (Waltons, Kochs, Murdoch, etc.)

Even those who appear to be in physical industries rarely make money making things. They make it by owning the rails that other people have to use.

Amazon doesn’t make. It routes.

Uber doesn’t own. It coordinates.

Spotify doesn’t produce. It gates.

Substack doesn’t write. It skims.

And when someone does build something physical?

They aren’t rewarded until they financialize it, until they IPO, until they gamify valuation, until they layer in data, subscriptions, surveillance, or story.

The market doesn’t care about production. It cares about narrative, velocity, and rent. So no—you don’t become a billionaire by building factories. You become a billionaire by controlling bottlenecks, skimming value, and scaling fast enough that no one can stop you.

Because in this system? Risk and production are for suckers.

Welcome to “The Great Extraction”

The 2008 crash should have been a turning point.

It wasn’t.

It was a blueprint.

Wall Street got bailed out. Main Street got strip-mined. Millions lost homes, jobs, pensions—while the very institutions that engineered the collapse were handed blank checks and golden parachutes. No arrests.4 No clawbacks. No real consequences.

The message was clear: If you’re big enough to break the system, the system has little choice but to protect you.

But something even more profound happened in the years that followed.

Silicon Valley watched closely—and took notes.

They didn’t just rebuild the economy. They rebuilt the interface.

Not on production. Not on jobs. Not on ownership.

They built it on attention, friction, and behavioral surplus.

This is where capitalism morphed into something else.

You don’t own your music—you stream it.

You don’t own your software—you subscribe to it.

You don’t even fully own your car—features are locked behind monthly payments. Heated seats, remote start, navigation—each behind its own little tollbooth.

Ownership didn’t just become optional. It became a premium feature.

The average person is now a tenant in their own life. Everything is rented. Everything is conditional. You are perpetually one missed payment, one price hike, one algorithmic flag away from being locked out of the very things you thought you owned.

While everyone was distracted by apps, gig work, and "flexible lifestyles," private equity quietly bought the world.5

Your vet.

Your dentist.

Your grocery store.

The local gym.

The farm down the road.

Even your kid’s daycare.

These weren’t strategic growth plays. They were opportunistic acquisitions, financed by cheap money and built to flip.

By 2025, nearly one in four American businesses is owned by a financial firm—not a family, not a founder. And the goal isn’t to nurture them—it’s to strip them, flip them, and exit.

Cut labor.

Sell off real estate.

Consolidate vendor contracts.

Repackage the debt.

Exit with a 3x return in 3 years.

This isn’t capitalism.

It’s controlled demolition, executed in slow motion and wrapped in language like “efficiency,” “synergy,” and “unlocking shareholder value.”

It’s how Toys “R” Us went under. It’s how SEARS went under. The list is quite impressive: A&P, Brookstone, Envision Healthcare, Friendly's, GenesisCare, Hudson's Bay Company, Instant Brands, Joann, Kmart, On the Border Mexican Grill & Cantina, Party City, Payless Shoe Source, Prospect Medical Holdings, RadioShack, Red Lobster, RJR Nabisco, Sports Authority, Steward Health Care, TGI Fridays, Thames Water, The Limited, True Value, TWA, and Vice Media.

All of them were pushed into bankruptcy and were profitable when they were acquired by venture capital.

And you, the consumer, the worker, the patient, the neighbor?

You’re not part of the equation.

You're the yield.6

The Digital Plantation

What do we call it when:

Labor is abstracted.

Ownership is eliminated.

Value is extracted.

And identity becomes the commodity?

We used to call that slavery.

Today, we call it the “Creator Economy.”

But you don’t own your platform. You don’t control the algorithm. You produce things that makes someone else rich—while fighting for scraps of visibility.

It’s the same model Uber drivers operate on. Or Instacart shoppers. Or Airbnb hosts trying to make the mortgage on a house they used to own.

The entire Substack model is predicated on this idea: fight for attention, fight for subscribers, fight for revenue.7

The system doesn’t need your body. It needs your time. Your output. Your brand.

And most of all—your compliance.

You’re not the creator.

You’re the content.

Welcome to the Matrix, Neo.

So Now What?

You’re not crazy for feeling like none of it makes sense.

Because it doesn’t.

You’re doing everything “right” in a system that no longer rewards the right things. You’re working, saving, building—and still falling behind.

Because this system isn’t built for prosperity.

It’s built for extraction.

The goal now isn’t to win the game. It’s to see the game.

And maybe—just maybe—build something outside of it.

Because you’re not losing.

You’re being harvested. You’re the yield.

If we’re being honest, there’s no going back.

You can’t vote this away.

You can’t hustle your way out of it.

You can’t fix a system that isn’t broken—because it’s working exactly as designed.

What we call capitalism today is just the brand language of power. A comforting story we tell ourselves while the real economy becomes something colder, thinner, and more extractive.

You navigate post-capitalism by understanding its logic. And refusing to play by it when you don’t have to. You stop chasing scale, virality, and reach.

You start chasing sovereignty, resilience, and leverage. These are the new objectives in the “post-capitalist” system.

You focus on:

Owning your income (not renting it through a platform).

Building tight networks (not mass audiences).

Avoiding debt traps and platform dependencies (because they’re built to skim).

Creating things with enduring value—not for hype, but for durability

You won’t outscale Amazon. You won’t outdo TikTok. You can’t become the next Airbnb. You probably won’t be launching dick rockets into space. But you can build outside of them—in the cracks, in the margins, in the places they can’t see and don’t care to go.

That may be where a good idea takes root.

This isn’t a return to some imagined utopia. It’s the beginning of something more challenging. But also something more fundamental.

We’re not going back to capitalism as you knew it.

We’re moving forward into something unwritten. Perhaps Historians and Economists will call it “Post-Capitalism " or “Extractionism.”

And the only way to survive it—

Is to stop being the yield.

And start being the one who writes the rules.

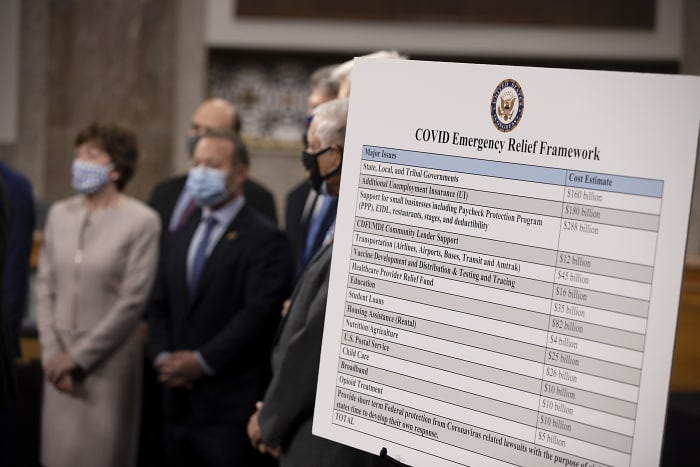

Post Script: To demonstrate “you are the yield,” I conducted a little experiment on Saturday (March 28, 2025). I posed this image at about 2 PM on Saturday:

The post received roughly four thousand views and about 250 interactions (likes, shares, comments, etc.).

Only two people correctly identified the post as fake.

I’m sorry I had to run that, but I wanted to know in real time how easy it might be to manipulate the audience to “get what I wanted.”

It was beyond easy. The post was up for eight hours, had virtually no context, and was designed to get people to interact, which it did. All I had to do was play on your (my audience’s and Substack’s) baser interests. I pulled the algy’s chain, and out popped attention.

Imagine now: It’s TikTok, I’m the Chinese Government, and a national crisis is about to unfold. This is not unique to TikTok, as the U.S. Government claimed in its briefings before the Court, but TikTok perhaps has the most threat because it has the widest audience reach and the fastest velocity to “harvest the yield.”

Again, two out of 4000 (roughly), spotted the bait as bait. That means only half of 100th of a percent of you thought critically about it, versus just reacting to it.

I put out the bait, and you all just CHOMPED HARD like a trout on a fly lure.

Don’t feel bad. The Washington Post put legendary violinist Joshua Bell in the Metro. He was passed by THOUSANDS of people, some of whom had paid $100 or more to hear him perform that month in D.C.

Hopefully, this convinces you of one thing, if you’re not awake: You are the yield.

Wake up.

This is an open post because this conversation needs to happen. If you want to support work like this and unlock deeper strategies for surviving post-capitalism, consider becoming a subscriber.

It wasn’t quite that way for me. I didn’t stand up and shout “JESUS TAP DANCING CHRIST!” and cartwheel out of my office like I just saw the light in a Chicago church. That might’ve been more impressive. Metaphorically, maybe I did.

The truth is, this is something I’ve struggled with for a long time—as an economist, as a builder, as someone who cares about systems that are supposed to work. That nobody gets rich making things anymore. That the wealth gap grows no matter what. That people like Musk float to the top while people who create real value sink beneath the algorithm.

I mean, I can wrap my head around Bezos. I can understand Gates, Buffett, or even the Sausage King of Chicago being rich.

But so many of these guys? I’d look at them and just think, “Huh?”

And then it hit me.

Like a ton of bricks.

The rules of the game haven’t just changed—they’ve been replaced. And I’d been playing the old game… in a world that had already moved on to a new one. In the end, I realized, I’m trying to play “Gimme some lovin,” when I was supposed to be playing “Rawhide!”

Rentier capitalism refers to an economic system in which wealth is primarily accumulated not through labor or productive enterprise, but through ownership of assets that generate passive income—like real estate, intellectual property, data, or digital platforms. The term “rentier” comes from 19th-century economics, originally used to describe individuals who lived off income from land or investments.

Classical economists like David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill distinguished between productive capital (used to create goods) and economic rent (unearned income derived from scarcity or monopoly). Later, Karl Marx criticized rentier classes as parasitic, extracting wealth without contributing value.

In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes famously predicted the “euthanasia of the rentier,” believing that mature capitalism would make rent-seeking obsolete. Instead, the opposite happened. In today’s economy, platforms, financial firms, and tech monopolies extract value not by producing things—but by owning the gate you have to pass through to access them.

Modern thinkers like Guy Standing and Michael Hudson argue that we now live in a rentier economy where extraction—via fees, licenses, interest, subscriptions, and platform control—has replaced production as the dominant economic model.

Between 2000 and 2020, the United States lost approximately 5.8 million manufacturing jobs, dropping from 17.3 million to just under 11.5 million. This wasn’t due to a sudden collapse in consumer demand for goods. It was driven by a combination of offshoring, automation, consolidation, and a broader shift in capital allocation toward financial markets, tech platforms, and rent-seeking business models. Manufacturing as a share of U.S. GDP has also steadily declined—from around 16% in 1997 to under 11% by 2020. In short: the jobs didn’t vanish. They were systematically devalued by an economy that decided speculation was more efficient than production.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED); Brookings Institution.

Well, not entirely true. Only one Wall Street banker went to prison for crimes related to the 2008 financial collapse: Kareem Serageldin, a mid-level executive at Credit Suisse. He was the Global Head of Structured Credit Trading and was convicted of conspiring to inflate the value of mortgage-backed securities on the firm’s books as the housing market unraveled. In 2013, he was sentenced to 30 months in prison. Serageldin became the lone symbol of accountability in a crisis that caused millions of foreclosures and trillions in economic damage. No CEOs, senior executives, or architects of the systemic fraud that fueled the crash were ever charged. As Serageldin later admitted, he was a scapegoat—punished not for the crime, but to give the illusion that someone paid the price.

Between 2010 and 2022, private equity firms acquired an estimated 40,000 U.S. businesses—everything from veterinary clinics and dental offices to grocery stores, funeral homes, home services, and daycare centers. By 2023, private equity controlled over 25% of U.S. hospital emergency departments, nearly half of all nursing homes, and growing shares of retail and food supply chains. These acquisitions are typically financed with debt, with the goal of extracting short-term returns by cutting labor, consolidating operations, and selling off real estate. The result: rising costs for consumers, deteriorating service quality, and a local economy increasingly owned by invisible financial operators with no long-term stake in the communities they extract from.

Sources: American Prospect, Brookings Institution, Private Equity Stakeholder Project, Wall Street Journal.

I imagine there might be some confusion about what I mean. In financial terms, "the yield" is the return generated by an investment—interest, dividends, or gains extracted from an underlying asset. In a post-capitalist context, you are the underlying asset. Your labor, data, time, attention, behavior, and compliance are monetized across platforms, algorithms, and financial structures. You're not the customer. You're not the owner. You're the instrument from which value is continuously extracted. You’re the yield on someone else’s investment.

Not to toot my own horn—I’m not just guilty of playing this game, I’m a fucking ninja master at it. Consider my situation: I went from zero to hundreds of paid subscribers. From zero to over 7,000 total subs. In 56 days. With no media presence, no built-in audience, no marketing, no trickery, fuckery, or fraud. I didn’t even use my real name. There was no bio to vet. No LinkedIn trail. Just the writing. Just the rhythm. Just my ability to read the audience and deliver what they didn’t know they needed.

I’m a Substack unicorn, if ever there was one.

So yeah—I’m not just guilty. I’m elite at this.

And that’s why I wrote this piece. Not as some outsider critique. But as someone who mastered the game and then looked up and thought: “Wait. This is the game? How do I, or even can I, win?”

This is a most lucid explanation—and very disheartening. It feels like the exploitative forces arrayed against us as individuals are overwhelming. What should we do to push back?

YES YES YES YES

I appreciate the deep dive - it helped me connect the dots on a deeper level. It's challenging to encourage people to opt out of extractive systems! This is incredibly helpful. I firmly believe going small is the best way forward at this point. Rebuild our own platforms. Invest in our local communities. Opt out of the creator economy or at least own your own platform and extract value from tools like Etsy and Substack in tandem before they collapse under their own weight.