A reader of one of my commentaries, “Who Owns Substack,” responded with:

"Not to be all communist and stuff—but Karl Marx predicted this."1

I think that was a dig at me, but I wasn’t entirely sure. If you read my reply, you’ll see my confusion. Was I supposed to clutch my pearls (if I was a woman and had pearls)? Reconsider my entire worldview? Maybe quote Adam Smith in retaliation?

This isn’t my first rodeo with that line of thinking. When I taught, I’d get some college kid explaining “the system, man” to me—usually while wearing Nike sneakers and a Che Guevara T-shirt they bought from some faceless corporation online. Irony is dead.

My business partner, an avowed leftist, likes to hit me with the “end-stage capitalism is ruining the world” monologue every time we’re in a cocktail lounge. Between sips of single malt whiskey, of course. We’re skipping the part where capitalism has provided more food, medicine, and wealth than any system in human history—but sure, let’s start the revolution right after this round.

And yet, here we are. A criminal billionaire is now President of the United States, flanked by a sidekick who could generously be described as a mentally impaired Bond villain. Their grand vision? Micromanage the economy and the government in the name of “capitalism”—efficiency be damned.

Naturally, the backlash from the likes of Bernie Sanders is that this isn’t capitalism at all—it’s oligarchy run wild.

So, let’s ask the fundamental question: Is capitalism inherently broken? Was Marx right? Not the Substack commenter. Not the Che-shirt kids. But the fundamental idea—Marx’s original premise—that capitalism is doomed to self-destruct, consuming everything in its path, including itself.

Let’s dive in.

What Was It That Marx Actually Argued?

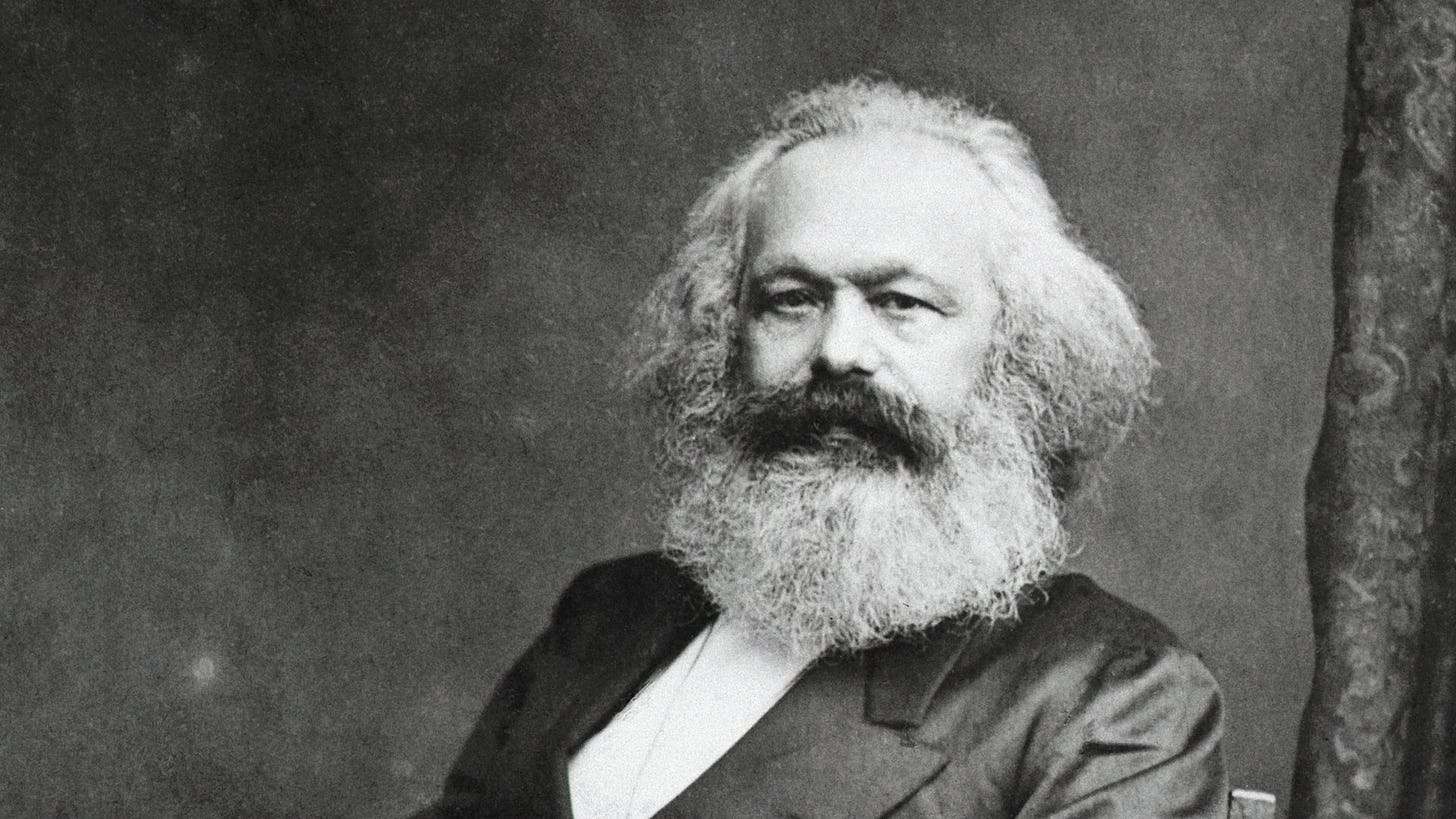

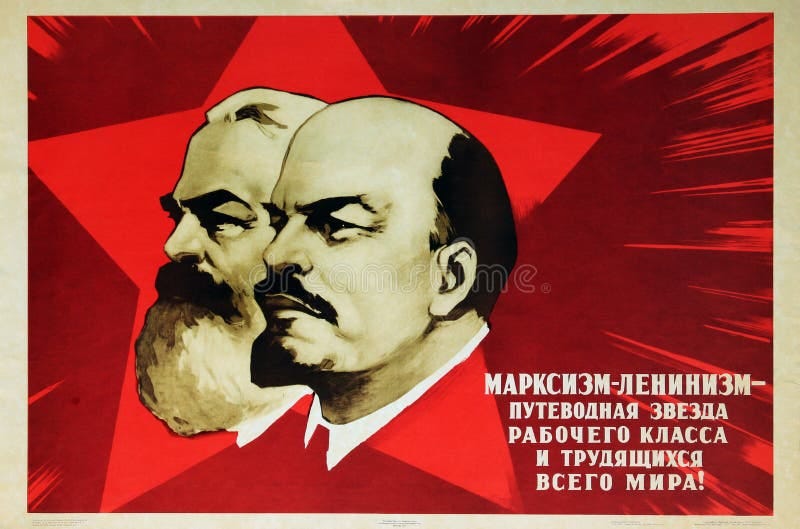

Karl Marx has become an intellectual Rorschach test—people see in him whatever they want. To some, he’s the prophet of the worker’s revolution. To others, he’s the guy who ruined Venezuela. But if we strip away the political baggage and the overzealous fanboys, what was Marx actually saying about capitalism?

At its core, Marx’s critique of capitalism wasn’t just “rich people bad.” His argument was far more systematic, rooted in his theory of historical materialism, which says that economic systems evolve in predictable ways—each carrying the seeds of its destruction.

Here’s the basic premise:

1. Capitalism Is Built on Exploitation

According to Marx, capitalism thrives because business owners (the bourgeoisie) extract profit from workers (the proletariat) by paying them less than the value they create. That difference—what he called surplus value—allows capitalists (the people who own the modalities of production) to accumulate wealth while workers (the people making “the stuff”) remain stuck in a cycle of survival wages.

2. Class Struggle Is Inevitable

Because capitalism depends on exploitation, Marx argued that conflict between the capitalist and the working classes was not just common—it was baked into the system. As capitalists chase profit, they squeeze wages, cut costs, and push workers harder, leading to growing discontent and, eventually, resistance.

3. Capitalism Consumes Itself

Here’s where Marx goes full doom-prophet: The better capitalism works, the closer it gets to collapse. Why? As businesses compete, they become more efficient, replace workers with machines, and drive wages lower. However, low wages mean workers can’t afford to buy the goods capitalism needs to sell. This creates a crisis of overproduction—too much stuff, not enough buyers. Profits shrink, businesses collapse, and economic crises become unavoidable.

4. Boom and Bust Cycles Get Worse Over Time

Marx predicted that capitalism wouldn’t just have the occasional economic downturn but create increasingly more profound economic crises as competition intensified. Companies would either swallow each other up (monopolization) or fail spectacularly, leading to mass layoffs and financial instability. These cycles wouldn’t just be growing pains but proof that capitalism was inherently unsustainable.

5. The Workers Eventually Rise Up

Here’s the part every freshman political science major loves: Workers UNITE! The inevitable revolution. As inequality worsens, wages stagnate, and the working class becomes more aware of their exploitation (class consciousness), Marx predicted that capitalism would collapse under the weight of its contradictions. Having nothing left to lose, the workers would overthrow the system, seize the means of production, and establish a socialist economy that redistributes wealth more equitably.

So… Was He Right?

Marx’s argument wasn’t that capitalism would fail overnight. He saw it as a historical process—just as feudalism gave way to capitalism, he believed capitalism would eventually give way to socialism. But looking around today, we see a few things he got right (wage stagnation, wealth concentration, economic crises) and a few things he didn’t foresee (capitalism’s ability to adapt, regulatory interventions, the rise of a global middle class).

But before we get into whether capitalism is dying or just evolving, let’s look at how we got from Marx’s 19th-century world to today’s economic reality.

From 19th Century to 1980: How Capitalism Adapted (For a While)

Karl Marx looked at 19th-century capitalism and saw a violent, exploitative, crisis-prone, and ultimately self-destructive system. And to be fair, that’s precisely what it was. The Industrial Revolution created immense wealth but also crushing poverty, child labor, horrific working conditions, and regular economic crashes. There were no labor laws, no minimum wages, and no safety regulations—capitalism in its purest form was a brutal free-for-all.

And yet, capitalism didn’t collapse the way Marx predicted. Instead, between his time and the late 20th century, capitalism mutated, adapted, and was forcibly restrained. The system that existed in 1980—the peak of post-war economic stability and middle-class prosperity—looked very different from the dog-eat-dog world of the 1800s.

So, what happened? How did capitalism avoid collapse and, for a while, actually work?

1. The Rise of Organized Labor (Late 19th - Early 20th Century)

If you want to know why capitalism didn’t implode in the 19th century, the answer is organized labor.

Workers started fighting back. The late 1800s saw massive labor movements, violent strikes, and socialist uprisings in industrialized countries.

Governments got scared. As strikes and riots grew more intense, some leaders realized they had two choices: reform capitalism or risk revolution.

Labor laws were passed. By the early 20th century, industrialized nations began instituting:

Limits on working hours (bye-bye, 14-hour shifts)

Child labor bans (no more 8-year-olds in coal mines)

The right to unionize (workers could now negotiate pay and conditions)

This didn’t happen because capitalists became benevolent but because workers fought for it. In democratic nations, politicians had to respond to labor power lest they get voted (or overthrown) out of office.

Why this mattered: Instead of collapsing, capitalism became slightly less horrible, which prevented workers from revolting outright.

2. The Great Depression & the Birth of Regulated Capitalism (1930s - 1940s)

Marx said capitalism would eventually implode under its own contradictions—and in the Great Depression, it almost did.

The stock market crashed in 1929, leading to mass unemployment, poverty, and banking failures.

Banks collapsed, wiping out people’s savings overnight.

Capitalism was in crisis, and many people thought the system was done for.

This was a turning point: Instead of allowing capitalism to self-destruct, governments stepped in to save it—but with strict new rules.

The U.S. created the New Deal. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration regulated banks, created Social Security, and established labor protections.

The Federal Reserve was strengthened. Central banks took on a bigger role in managing financial crises to prevent total collapse.

Glass-Steagall separated investment and commercial banking. The era of reckless speculation was (temporarily) over.2

For the first time, capitalism was not just left to run wild—it was tamed, regulated, and forced to operate in a way that reduced instability.

Why this mattered: Capitalism survived by becoming less capitalist—it now had rules, safety nets, and a state willing to intervene when necessary.

3. Post-WWII: The Golden Age of Capitalism (1945 - 1980)

After WWII, capitalism entered a period that Marx would have never expected: relative stability, broad prosperity, and a strong middle class.

Unions were powerful. Around one-third of workers in the U.S. and Europe were unionized, giving labor real negotiating power.

The economy boomed. Productivity soared, wages increased, and a strong middle class emerged.

Mass consumerism became a stabilizing force. People had money to spend, and businesses catered to growing consumer demand.

Governments also played a key role:

High taxes on the rich kept wealth inequality in check.

Strong financial regulations prevented reckless speculation.

Government investment in infrastructure (highways, public education, social programs) created economic stability.

For a few decades, capitalism actually seemed to work. It still had problems (racism, gender inequality, environmental destruction), but the balance between labor, capital, and government created an era of unprecedented economic growth.

Why this mattered: By managing capitalism—regulating businesses, redistributing wealth, and maintaining worker protections—society avoided the crisis cycles that Marx had predicted.

4. But Then… The 1980s Happened.

If the story had ended in 1980, you could almost argue that capitalism had permanently solved its contradictions. But capitalism’s survival strategy came with a fatal flaw:

The same business elites who had been forced to accept these regulations never stopped trying to undo them.

They hated high taxes.

They hated powerful unions.

They hated financial regulations.

And by the late 1970s, they saw an opportunity. Enter: Milton Friedman.

Next: 1980, Milton Friedman, and the Return of Raw Capitalism

From the New Deal to the 1970s, capitalism functioned under a regulated model—balancing labor, capital, and government intervention. But in 1980, that all changed.

Milton Friedman and neoliberalism emerged, pushing the idea that business should care only about profits, not society.

Reagan & Thatcher dismantled regulations, cut taxes on the rich, and attacked unions.

Globalization made labor easier to exploit, as jobs were offshored to cheaper markets.

This was the turning point. From 1980 onward, capitalism stopped trying to balance itself with labor and regulation—and we returned to a system that looks more and more like what Marx warned about.

1980 & Milton Friedman: The Man Who Changed the Game

If you want to pinpoint the moment capitalism stopped playing nice, look no further than 1980. Up until then, the system had been running on a post-war compromise:

Businesses made profits but dealt with strong unions and high taxes on the wealthy.

Workers got good wages and benefits but within a capitalist framework.

Governments regulated finance and industry to prevent the chaos of the Great Depression.

It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. And then along came Milton Friedman, free-market evangelist and architect of modern neoliberalism, who decided that this whole “balance” thing was a terrible idea.

Friedman’s Big Idea: Profits Over Everything

Milton Friedman’s most influential idea was shareholder primacy—the belief that a company’s only responsibility is to maximize profits for its shareholders. Not workers, not communities, not society—just profits.

In his 1970 essay The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits, Friedman declared that any corporate leader who considered ethics, workers, or the environment was betraying capitalism.

He rejected the post-war balance of labor and capital, arguing that taxes, regulations, and unions hindered economic growth.

His vision? Strip capitalism down to its rawest form—businesses operate with no restraints, governments step back, and “free markets” solve everything.

The Reagan-Thatcher Revolution: Deregulation & Union Busting

Friedman’s ideas would’ve just been academic theory if not for the political leaders who took them and ran with them:

Ronald Reagan (U.S.) & Margaret Thatcher (U.K.)

Slashed taxes on the rich – The top tax rate in the U.S. dropped from 70% to 28% under Reagan.

Deregulated finance – Restrictions on Wall Street were rolled back, setting the stage for the future 2008 crash.

Crushed labor unions – Reagan fired striking air traffic controllers in 1981, signaling that corporate America could attack labor without consequences.

Privatized industries – Public services were handed over to corporations, who promptly turned them into profit machines.

This wasn’t a minor policy shift—this was a fundamental rewrite of capitalism.

The old social contract (shared prosperity, worker protections) was shredded.

The era of “trickle-down economics” began.

Corporations, no longer restrained by regulation or unions, exploded in power.

The Financialization of Everything

With regulations gone, corporations stopped investing in workers and production and instead focused on… finance.

Stock buybacks replaced wage increases. (Why pay workers when you can boost share prices instead?)

The rise of private equity stripped companies for parts.

Debt-fueled speculation turned Wall Street into a casino.

Instead of producing things, capitalism became obsessed with making money from money.

Globalization: The Final Nail in Labor’s Coffin

The 1990s took Friedman’s vision global:

Free trade agreements (NAFTA, WTO) made it easier for corporations to move jobs overseas.

Manufacturing collapsed in the U.S. as companies chased cheap labor in China and Mexico.

Labor power was gutted—how can workers negotiate higher wages when jobs can just be offshored?

The result? A new kind of capitalism. One that looked less like the post-war boom and a lot more like the world Marx described—a handful of billionaires extracting maximum profit from a weakened, disposable workforce.

Next: The Slow Slide to Now

From 2000 to today, the contradictions of this new capitalism have only deepened:

Wages have stagnated while CEO pay has skyrocketed.

2008 exposed the instability of deregulated finance, but nothing fundamentally changed.

Monopolies dominate entire industries, killing competition.

The “gig economy” resurrected 19th-century labor exploitation—no stability, no benefits, no future.

So now we have to ask: Did the neoliberal revolution delay the inevitable collapse of capitalism, or are we now finally at the breaking point Marx predicted?

The Slow Slide to Now: Are We Finally Seeing Marx’s Prediction Come True?

From 1980 onward, capitalism stopped pretending to care about balance. The labor-capital compromise of the post-war era was dismantled, and the neoliberal model of deregulation, shareholder primacy, and globalization took over. For a while, it looked like a success—the stock market soared, technology boomed, and a new class of billionaires emerged.

But beneath the surface, the cracks started to widen. And now, four decades later, we’ve arrived at a moment that looks eerily familiar—not to 1950, but to the late 19th century, the world Marx wrote about.

1. Wages Stagnate, Inequality Explodes

Since 1980, wages for workers have barely budged, while CEO compensation has increased over 1,200%.

The richest 1% now control more wealth than the bottom 90% combined.

Billionaires saw their net worth skyrocket during economic crises, while average workers struggled to survive.

Marx’s idea of capital accumulation—where wealth concentrates at the top while workers get squeezed—has played out in real-time.

2. Boom, Bust, and Bailouts—The Economy Looks More Fragile Than Ever

The 2008 financial crash showed that capitalism is still crisis-prone. But instead of a full collapse, governments bailed out the banks while ordinary people lost their homes.

COVID-19 revealed just how precarious the system had become. Billionaires got richer while millions of workers were deemed “essential” but barely got a raise.

Inflation, tech layoffs, and economic uncertainty today suggest we’re still on unstable ground.

The old pattern has returned: profits are privatized, losses are socialized. Workers absorb the pain, while corporations and the ultra-wealthy walk away richer.

3. The Rise of Monopolies & the Death of Competition

In Marx’s time, industrialists like Rockefeller and Carnegie dominated entire industries. Today, we have:

Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google controlling the digital economy.

BlackRock and Vanguard owning massive chunks of the financial system.

Private equity gutting industries, turning basic services into profit centers.

The result?

Small businesses and entrepreneurs struggle to compete.

Wages stay low because there’s nowhere else for workers to go.

Political power is concentrated in a handful of corporate players.

Capitalism was supposed to be about competition. Instead, it’s drifting toward oligarchy—exactly what Marx predicted.

4. Labor Struggles Return—But in a Weaker Position

The one thing that saved capitalism last time was organized labor. But after decades of decline:

Union membership is at an all-time low.

Gig workers have fewer rights than factory workers did in 1900.

Companies like Amazon and Starbucks aggressively fight against worker organizing.

There are signs of a new labor movement—strikes at big corporations, a push for unionization—but they’re fighting against a much more powerful corporate structure than in the past.

5. Politics Has Been Bought—The Wealthy Rule

The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision (2010) allowed unlimited corporate money in politics.

Billionaire-funded think tanks shape economic policy.

The ultra-rich now openly buy influence, backing candidates and policies that serve their interests.

Instead of democracy restraining capitalism, capitalism has absorbed democracy.

So… Are We At the Endgame?

For all his insight, Marx was wrong about one thing: Capitalism didn’t collapse on its own. It survived by adapting—through labor movements, regulations, and government intervention.

But over the last 40 years, we’ve undone those guardrails. And now?

Inequality is worse than at any point since the Gilded Age.

Workers are losing power while corporations consolidate.

Boom-bust cycles are getting worse, and the economy is increasingly unstable.

So the real question isn’t “Was Marx right?”—it’s “How long can we keep pretending he wasn’t?”

If history tells us anything, capitalism either adapts again… or it collapses. The only question is what form that next adaptation—or crisis—will take.

The Consequences of Where We’re Going

For the past forty years, capitalism has been running on borrowed time. The system that once balanced labor, capital, and government intervention has given way to something far more volatile—an economy that prioritizes financial speculation over production, corporate dominance over competition, and short-term profits over long-term stability.

The warning signs are flashing. The social contract that once held everything together is unraveling. The consequences of this trajectory aren’t hypothetical—they’re already here, shaping the world we live in today. If the current system doesn’t correct itself, these trends will only accelerate.

A Permanent Class Divide is Solidifying

One of capitalism’s core promises was mobility—the idea that hard work and innovation could lift anyone to prosperity. That promise is breaking down. Home ownership, once the foundation of middle-class stability, is increasingly out of reach for younger generations. Wages have stagnated while costs for education, healthcare, and housing have soared. Instead of climbing the economic ladder, most people are running in place, if not sliding backward.

The new economic reality is one where a small elite owns everything—housing, land, major industries—while the rest are locked into a cycle of renting, debt, and insecurity. Wealth isn’t just accumulating at the top; it’s becoming hereditary, passed down through dynastic fortunes while social mobility collapses. We’re moving toward a world where your birth determines your economic future, not your work.

Democratic Institutions Are Being Undermined

Wealth concentration doesn’t just skew economic outcomes; it distorts political ones as well. The ultra-wealthy don’t just hold financial power—they shape the laws, the policies, and even the candidates who get elected. When the Supreme Court ruled that money equals speech, it cemented the ability of billionaires and corporations to dictate policy without accountability.

As economic inequality deepens, so does political inequality. The public’s ability to influence government is fading, replaced by a system where lobbyists, dark money, and corporate interests call the shots. Elections become performative, a spectacle where candidates promise change but remain beholden to the donors who fund their campaigns.

History tells us that when economic and political power become too concentrated, faith in democracy collapses. People stop believing the system can work for them. That’s when alternatives—some democratic, some authoritarian—begin to emerge.

Monopolies Will Continue to Tighten Their Grip

The free market is no longer free—it’s owned. Industries that once thrived on competition are now dominated by a handful of corporations that set the rules, dictate wages, and control entire supply chains. Amazon dictates retail. Google owns search. BlackRock and Vanguard hold massive stakes in everything from tech to energy to real estate.

Small businesses and independent competitors are being crushed. There’s no innovation when a company can either buy out its competitors or starve them of resources. There’s no real job market when a handful of megacorporations decide how much labor is worth. Capitalism has drifted far from its supposed principles—it is no longer a system of risk and reward but one of entrenched, untouchable power.

Labor is Becoming Disposable

The dream of stable, long-term employment is fading. Companies have replaced full-time jobs with contract work, gig labor, and short-term employment that keeps workers permanently unstable. The “flexibility” of the gig economy has meant flexibility for corporations, not workers—flexibility to fire at will, to avoid providing benefits, to shift risks entirely onto individuals while maximizing profits.

With AI and automation advancing, even middle-class jobs are under threat. The future workforce won’t just be low-wage and insecure—it may be unnecessary. The Industrial Revolution created jobs even as it destroyed old ones. But what happens when machines don’t just replace factory workers but replace white-collar professionals, analysts, and even creative workers?

Social Unrest is No Longer a Hypothetical

When systems fail to serve the majority, people eventually push back. The populist wave of the past decade—Trump, Brexit, nationalist movements across Europe—wasn’t random. It was a reaction to decades of economic instability, rising inequality, and a growing sense that regular people have no control over their lives.

But anger is not ideology. It can manifest in right-wing authoritarianism, left-wing uprisings, or complete institutional breakdown. It can take the form of strikes, protests, political realignment—or, in extreme cases, violence against the perceived architects of economic oppression.

This is why cases like Luigi Mangione’s killing of Brian Thompson are so disturbing. They are early warning signs, moments when the pressure becomes too much for one individual to bear. But they won’t remain isolated acts. If the system continues on this path, the question isn’t whether more people will break—it’s how long the cracks can be contained before the dam bursts.

An Aside: Luigi Mangione & the Murder of Brian Thompson—A Symbol of a System Cracking

Every so often, a crime isn’t just a crime. It’s a rupture, a moment that lays bare the cracks in the system. The killing of Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione was exactly that—a flashpoint in an economy that has left too many people behind.

On the surface, it was just another act of senseless violence. A man with nothing left to lose took the life of a powerful CEO. But the details of this case—who the killer was, who the victim was, and the world that shaped them—tell a much deeper story.

The Players: Two Sides of the Modern Economy

Luigi Mangione wasn’t a monster. He was a man caught in the gears of a system that no longer had a place for him.3

He had a middle-class background, an education, and a belief that hard work still counted for something.

He did everything right—held down jobs and played by the rules.

Healthcare costs, constant pain, housing prices, unstable work—it all built up until he snapped. At least, that’s the story that appears to be the case.

Brian Thompson, on the other hand, was the face of the new economy.

A healthcare executive who had made his career finding efficiencies—which, in real terms, meant cutting costs, denying claims, and maximizing profit margins.

He lived in a world of bonuses, stock buybacks, and quarterly earnings reports, where shareholders mattered more than the people his industry was supposed to serve.

Two men, two entirely different experiences of capitalism—one struggling to survive in it, the other thriving by making it harder for people like Mangione to get by.

The Breaking Point

The specifics of what triggered Mangione to act are murky. Some say it was a rejected medical claim, others point to a denied appeal. What’s clear is that Mangione had reached the point of absolute despair.

He walked into a hotel lobby where Thompson was attending an industry event.

Two shots. One of the most powerful executives in America was dead.

Mangione fled, but was caught shortly after—his pockets filled with a manifesto railing against corporate greed and a list of other targets.

It wasn’t just a murder. It was a rage-filled response to a system that felt completely rigged.

The Fallout: A System Exposed

What happened next was just as telling as the crime itself.

Instead of universal condemnation, a strange, uneasy sympathy emerged.

Online, people asked, “What drives a man to do this?”

A legal defense fund exploded with donations, many from people who had been on the losing end of the healthcare system.

No one excused what Mangione did. But the fact that so many understood it?

That was the real warning sign.

Where Does This Lead?

The road ahead looks increasingly unstable.

The forces that held capitalism together—strong labor, democratic institutions, and regulation—have been eroded. The forces that could replace them—new economic models, new labor movements, new political frameworks—are still weak and fragmented.

If capitalism adapts, it will likely be through a return to regulation, public investment, and a recognition that extreme inequality is unsustainable. But if it doesn’t, then we are entering uncharted territory, where political instability, economic insecurity, and social unrest become the norm rather than the exception.

Marx argued that capitalism would eventually consume itself, that its pursuit of profit at all costs would create the conditions for its own destruction. For a long time, that seemed like an overstatement. But now? The consequences of unchecked capitalism are no longer just theoretical. They’re here. And whether the system corrects itself or collapses entirely is no longer an academic debate—it’s a choice we are all going to have to face, sooner rather than later.

Workers of the world… UNITE?

If you’ve considered upgrading to The Long Memo (TLM), now’s the time. Through February 28, annual plans are 25% off—for just $5 a month (billed annually). That means a full year of exclusive deep dives, analysis, book club access, and all future paid-member benefits—at the lowest price it will ever be. This deal won’t happen again.

If you’re already a paid subscriber, thank you for supporting the publication.

In my response to that reader, he argued that Marx’s lifelong financial struggles were proof of capitalism’s failure. My reply was simple: no, that was Marx’s own fault. He was a reckless spender, a chronic debtor, and a philandering writer who lived well beyond his means. If anything, he enjoyed “the good life” as much as his creditors would allow. An irony, perhaps, that the man who criticized capitalism and finance attempted to exploit it to its maximum benefit.

The repeal of Glass-Steagall may be one of the most catastrophic mistakes Congress ever made. It directly led to the 2008 financial collapse, has fueled multiple banking failures since, and created a system where banks are permanently “too big to fail.” By eliminating the distinction between depositor institutions and merchant banking, Congress didn’t just deregulate finance—it rigged the system to ensure that when reckless over-leveraging inevitably leads to disaster, taxpayers, not bankers, foot the bill.

I decided to edit this later on February 17, 2025 to make a few things clear. First, I wrote this section based on what was available about Mangione. His actual situation and motives aren’t well-known or documented. There are lots of articles that speculate as to what his motivations were, but very little is known for sure. Second, until there is a trial, we don’t know for sure. What appears to be the case is that Luigi Mangione was otherwise a regular guy who had back surgery, was a changed man as a consequence of that event, withdrew over some time, and then ultimately committed this act of violence (granted, he’s innocent until proven guilty; however, we have videotape evidence, we have witnesses to the act, Mangione was arrested with the murder weapon. I realize how the justice system works; however, let’s be practical in assessing his guilt as a factual issue, not a legal one.) More importantly, is not Mangione’s guilt or innocence per se as it is the public’s reaction to his alleged act. Not since Bonnie and Clyde have we seen the population at large cheer on murderers. Mangione’s defense team quickly raised hundreds of thousands of dollars through his crowdfunding page. The individual who tipped off the police received death threats for his act. This behavior demonstrates the point I am trying to make in this section of how this crime isn’t just a “crime” but a watershed moment in the “American psyche,” the way Bonnie and Clyde were in the Great Depression.

As I substance farmer with a government day job, I have been preparing to feed myself for decades now. Farmers are fewer in number than in times past, and more dependant on fossil fuel inputs for existing in the current capitalist system. Find and support your local farmer if you like eating. Or produce something you can eat in your spare time. Now. A friendly suggestion.

One big piece of missing information in this essay is the environmental degradation accompanying all resource extraction. The absence of strong links between the economic theories of "market growth" and the biological realities of growth and extinction that keep every single person on the planet alive, are a hidden source of additional short- and long- term instability. The war on Science has the goal of keeping these links hidden, but it won't halt the perturbations made in the dynamics of all the underlying Earth systems from more than two centuries of intensive resource extraction and lack of waste stream management.

As far as I can tell, only the insurance industry seems concerned, since they are in the business of compensating their clients for losses of all sorts from diseases to disasters. The costs are being tracked by them.