Leaving Wasn’t the Plan

Packing Guilt Along With the Luggage - A cross-post feature with Borderless Living.

A Preface

This is a cross-post with my other Substack, Borderless Living. Apparently, if you have two Substacks, you can’t cross-post between them—which seems silly—so I’ve republished today’s post from Borderless here in full.

The Long Memo and Borderless Living are symbiotic. The Long Memo explores the “why” behind everything falling apart. Borderless Living is more about the “how”—what to do, where to go, and how to prepare if, like me, you believe the system won’t correct itself.

I know leaving isn’t for everyone. For most, it’s not even about logistics—it’s about emotion. It’s about the ache, the internal conflict, the guilt. That’s what this piece is about.

I did my bit for God and Country. I don’t believe the dominoes are going to stop falling. I don’t think the next election is going to fix what’s broken. Looking back, this may be the final chapter of changes set in motion 40 years ago. Maybe this is the real reason “we can’t have nice things.”

No amount of being right about any of this feels comfortable when principles become punishment and expression becomes repression. That’s the brutal truth of it.

There’s a reason so many people throughout history—intellectuals, journalists, reformers—ran before the walls closed in. They weren’t cowards. They just understood what you’re seeing now: when a regime crosses into authoritarianism, being principled becomes dangerous. Thought becomes threat. Clarity becomes crime.

If you see this as I do, you’re not paranoid. You’re early.

Many will disagree with that characterization. That’s fine. Some will say they’ll “die with their boots on.” I understand that instinct. Maybe that will be the last act of agency many Americans have before this is all over. But me? I’m reminded of what Billy Wilder said about those who fled Germany’s descent into Nazism:

“The optimists all died in the gas chambers. The pessimists all have pools in Beverly Hills.”

So for now, consider me a pessimist.

And the sick part is, being early feels crazy—right up until it doesn’t. Until it’s too late. The ones who stayed behind, hoping they were overreacting, are the ones history forgets—or remembers in whispers.

So no, being on the right side of history won’t save you if you’re lined up at the wall.

But leaving before the guns come out might.

And building a life elsewhere that lets you keep thinking freely, keep writing, and maybe—just maybe—help others see what’s coming?

That’s the win.

This post is about the grief that hits before you leave. The kind that settles into your chest when you realize the country you love might no longer be safe for you. You might have to go—not because you stopped loving it, but because it stopped being what it promised.

You’re not alone in feeling that.

I wrote this piece for those of us quietly carrying that weight. I know that’s why many who subscribe to The Long Memo read it—they’re quietly hoping we’re all wrong.

You’re not alone in that either. But if we’re honest, deep down, we know we’re not wrong.

This is happening.

And the ending of this movie is one we already know too well.

I haven't even left yet, and I'm already grieving. Not just for what I'm contemplating leaving behind—but for what it says about the place I used to believe in.

I know many others feel that way. I read it on Reddit and Substack.

It’s not like going on vacation. I have no doubt you felt excited to explore new lands and places while on vacation.

There was always a grounding of “home” to return to.

I don’t know about you, but as someone who worked for the US Government, I know where our embassies around the world are located. There is something comforting about walking by the US Embassy abroad as an American and seeing the Great Seal or the stars and stripes flying high, even though you’re excited to be in Rome, London, Paris, or somewhere else in the world.

It feels like a betrayal even to be exploring the options.

If you feel that way, you’re not alone. I feel that way. Tens of thousands of others do. Why? I can’t explain it just yet. I mean, I can at an intellectual level, but not an emotional one.

So, to understand you’re not alone in feeling this way, I wrote this piece.

A particular ache comes not just from leaving, but from realizing you might have to. It’s a grief that settles into your chest long before the plane ticket is booked, long before the house is sold, or the citizenship paperwork is filed. It’s the grief of watching the ground shift beneath your feet—of realizing the place that shaped you might no longer be safe for you.

And the hardest part? It’s not like you suddenly hate your country.

That would be easier, honestly.

What makes it so heavy is that you still love it. Memories are embedded in the soil—childhood summers, Fourth of July fireworks, late-night drives down familiar roads. That you still feel something when you see the flag—even if that something is complicated now.

It’s like watching a parent decline. They’re still them, but… not really. And even if they can no longer protect you, even if they’ve started to hurt you, you feel guilty for stepping away. For choosing safety over sentiment. For doing what you have to do.

And yet, people are choosing.

Quietly. Cautiously. Sometimes anonymously. They’re researching dual citizenship. Looking into bank accounts abroad. Scouting schools in Portugal, Ireland, or New Zealand. They’re not packing in a panic—but they’re preparing. And under all of it, there’s this same aching question:

“Am I betraying something by leaving?”

That guilt is baked into us. It’s how nationalism works. We’re raised to believe America isn’t just a place—it’s our identity. A team. A mission. And walking away from it feels like walking away from a fight. From your people. From your past.

But what if staying means surrendering more?

What if the true betrayal isn’t leaving… but silencing your instincts and pretending it’s all going to be okay?

That’s the space I’m sitting in. And maybe you are as well.

I don’t have clean answers. I know this grief is real. And if you're feeling it, you’re not broken. You’re not disloyal. You’re not weak.

You’re awake.

And you're not alone.

I want to share some of the thoughts I’ve considered as a scholar, a commentator, and as someone who took an oath to defend the Constitution of the United States.

Because this decision—this contemplation of leaving—isn’t just personal. It’s political. It’s constitutional. It’s existential.

For those, like me, who have taken the oath, it wasn’t to a president, a party, or a flag. It was to an idea—a fragile, powerful idea—that liberty and justice could be preserved through a system of checks, balances, and the rule of law. And we believed in that system, deeply. Some so much so, they gave their lives for its protection.

We still want to believe in it.

But belief without evidence becomes faith. And faith in the absence of accountability becomes delusion.

We’re watching institutions decay from the inside—norms erode, courts bend, laws twist, and truth become optional. We’re watching power centralize in ways that can’t be undone with an election. And we’re watching how quickly fear is being used to justify repression. I write about it nearly daily at The Long Memo. That project started partly because I needed an outlet for the emotions bottled up, watching the news daily, seeing what was about to happen to my colleagues, and hoping that rousing the public to action might stem what was about to be unleashed.

We’d know what to call it if it were happening anywhere else.

But because it’s here, we hesitate. We tell ourselves, “It can’t happen in America,” as if geography is immunity. As if the Constitution is self-enforcing. As if good people always win.

That’s why I felt compelled to write “The Erasure of America.” I felt something like Sinclair Lewis’ “It Can’t Happen Here” wasn’t accessible to most people.

I mean, I get it. MILLIONS of people came here seeking a better life. Nobody chastizes them. Nobody says they made the wrong decision. Nobody says to the guy who flees oppression, “Well, you should have stayed at fight!”

Nobody says that.

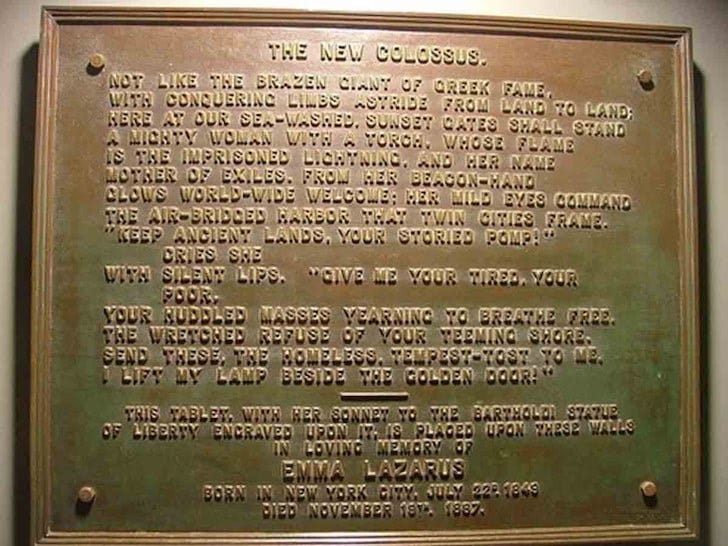

Millions come here, looking for a better life. Looking for better treatment. Looking to flee oppression. Emma Lazarus’ The New Colossus says it so well it winds up on our greatest icon, that welcomes the world to become American, The Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

But the truth is: no country is immune to authoritarianism. No system, no matter how elegant, survives without people who defend it. And right now, many of those people are exhausted, silenced, leaving, or gone.

I spent a good chunk of my life judging “geo-political risk,” professionally. If I were writing an intelligence brief on us right now, it wouldn’t be pretty. At best, we’re headed for anocracy. At worst, we descend into something that once felt unthinkable.

So yes, I’m grieving—not just for what I may be leaving but for the republic we all might already have lost.

Leaving, if it happens, won’t be because I stopped loving America.

It’ll be because I loved it too much to pretend this is normal.

America is the Greatest Country?

I think part of what makes this grief so disorienting is that it’s not just about geography. It’s not just a flag or a hometown or a passport.

It’s about the story we were told.

The myth of America wasn’t just taught—it was baked into us. Reinforced in classrooms, in movies, in rituals, in the language we used to talk about ourselves. We weren’t just a country. We were the country. The city on a hill. The beacon of liberty. The last is the best hope.

Even in Newsroom, the clip I’ve shared, the myth is “we aren’t the greatest country in the world, we were, and we could be again.” The entire Aaron Sorkin series was a suggestion that if the truth was made evident, that America would just sort itself out again.

Why? Because of course, America actually is the greatest country in the world, even if it temporarily lost her way.

And for a time, maybe that story served a purpose. Maybe it helped us strive to be better. Maybe it gave people something to believe in when the facts didn’t quite measure up.

And I will tell you this myth is something not just our people believed, but our allies, and even our enemies, believed worldwide.

I wasn’t at State, and I didn’t work on every issue while I was in government, but I did work on what was perhaps the most controversial issue of the Bush Administration. I worked with both diplomatic and military partners around the world. From my perspective, let me share a secret: in all the meetings I had with other countries, while they may say critical things about us in the UN or public spaces when the doors closed, it got down to “brass tacks,” the conversations inevitably changed.

What I experienced was one of two things: a private acknowledgment that the things we were doing as a country, while unpopular, did protect lives, protect our allies, and protect the peace of the global system.

If you’re abroad, in Europe, reading that and thinking, “no way,” YES WAY. Your government said that to us. They may have poo poo’ed us to you, but when the doors closed, they thanks their stars we were doing what we were doing most of the time.

Alternatively, I endured disgust at us for not living up to “Aunt Bea and apple pie” (from Andy Griffith.) Our British and French Allies, in particular, were always disgusted with me about that fact. While they thought we were naive and, at times, downright stupid, they couldn’t help but admire what was a genuine intent on the part of most of the people in government to be fair, honest, and forthright. It was because of those facts that our friends were angry with us because we failed to live up to our stated ideals.

I’m not saying we did things right, far from it. America is a land of strong contradictions and tensions. We suffer from an original sin tied to slavery and the contradictions of our founding. We have an arrogance in the belief our ideas are the best. We often jumped headstrong into problems without thinking through the consequences.

When I was a political appointee, I wore the seal of the US on my lapel abroad. I defended the US’ actions in international fora and in meetings around the world and before public venues. I called down the thunder on them. I made no excuses for my country. I challenged our friends, allies, and enemies to justify their hypocrisy because America was listening to the world, attempting to do what was right and aligned with its national security interests. Did we get it wrong?

All the time.

Despite all of that, our friends were painfully aware. They demanded that we live the myth of American exceptionalism because they desperately wanted to see the world we promised as well. In that regard, the idea of the American exceptional drove improvements around the world. It created fuel for change in many countries. It strengthened international coalitions. It made the world a better place.

But myths can be dangerous if they outlive their usefulness.

Because now, that mythology keeps us stuck instead of driving us forward. It’s convincing millions of people that nothing evil can happen here. That we’re immune. That the arc of history will bend toward justice without any help from us. If things truly fell apart, surely someone would stop them.

But no one is stopping it.

Because the myth has become armor. A shield against reality. A story we whisper to ourselves so we can sleep at night, even as the house burns down around us.

So yes, I’m grieving.

Not just for what I may leave behind.

But for the story I grew up believing—the story that made me love this place so deeply and now makes leaving it feel like sacrilege.

But stories can lie.

And when they do, you have to decide whether to keep living inside the lie… or start telling the truth.

Grief and preparation

My mother died about three months ago. When it happened, I didn’t grieve all that much. It’s a long story, but my relationship with my parents is “complicated,” to say the least. I imagine that’s true in most Italian-American families, at least it seems to be.

So as I said, I didn’t grieve all that much. Hardly anything, actually. I didn’t cry. I wasn’t upset. I dealt with things with my father at the hospital, who was of course devastated. Having been married myself for 30+ years, I can relate what that loss would mean. Yet, I still felt more or less nothing. It wasn’t particularly real to me.

My wife and children were wondering if I wasn’t having some kind of denial. I have to admit, I also wondered if I was engaged in some denial. Perhaps I was. I’m a stoic by nature, that is, until the procession at the church. At that moment, the weight of what had happened was inescapable. I almost exploded like a volcano. It took every ounce of control to regain my composure.

I had to; I was the first to speak following the processional—a reading from the Book of Wisdom (you undoubtedly know the passage.) I’m not even all that practicing of a Catholic (never was). Yet I have that reading memorized, and probably will, until my death.

Knowing that I might delaminate in that moment, or perhaps preparing for it subconsciously, I memorized that passage. I studied it carefully. I studied how others had delivered it. I rehearsed it. Rehearsed the delivery of it. I had the timing, the inflection, and the entirety of it mapped so that it would be second nature.

I’ve delivered thousands of speeches in my career. I’ve written hundreds of speeches for others. I mean, that’s what I did in my career for a period of time, including Presidents, cabinet officials, and other famous people.

Was all I could do, in that moment, to pull it together. I must admit, I have little conscious recollection of it. However, according to everyone in the church, including the clergy who were there, I brought down the house; something they had not seen with a simple biblical reading. The father said, “you would have made a good priest,” I replied, “I chose a different profession to use words to influence others.”

I had to stick the landing on that event. Despite the emotion, the grief, the gravity of the moment, it was what I had promised my father, and owed my mother, to do.

So in some ways, it was probably the most important speech I had ever given. And given whom I’ve written for, and whom I’ve addressed, that’s not a boast without context.

That’s how I feel about the task in front of me now. Pain and sadness cannot be an excuse for inaction and a lack of preparation. My wife and my careers are nearing their end, and my children are at the beginning of theirs. What will their lives be like if we stay? What will the opportunities be for them? What is their future like if I do nothing?

So, while I owe it to myself, I most certainly owe it to them.

CODA, for now

I don’t write this to tell you what to do. Only to say this: If you’re feeling this too—this ache, this guilt, this grief—you’re not imagining it.

You’re bearing witness to the end of something.

And in time, perhaps, the beginning of something else.

If you don’t prepare and take those steps, however, the chapter could be the final one written for you instead of by you.

J. M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, once observed: “The life of every man is a diary in which he means to write one story, and writes another; and his humblest hour is when he compares the volume as it is with what he hoped to make it.”

Consider me humbled. I’ve decided there’s no choice but to write another chapter. One that isn’t written for me but by me.

This piece is free because this conversation needs to happen. If you want to go deeper—into the practical steps of preparing to leave—consider subscribing to Borderless Living. That guide is coming soon. As always, thanks for reading, thinking, engaging, and supporting The Long Memo.

Thanks for putting a point on what many are thinking. I know I am. 68 years of this living does not prepare you to mentally think about leaving but with time being short the daily flow of horror is not how anyone wants to get to the finish.

This post resonated with me. I grieved when I left in 2017 and then again after the election results in November 2024. Once you no longer live in the U.S. and the Kool Aid is out of your system, you look gain a different perspective and suddenly some things now seem ridiculous, such as fighting with for profit insurance companies for basic healthcare, how some things can be legal in one state but illegal in another (and my husband and I are both lawyers and have sat for bar exams in 3 different jurisdictions each - can't believe we didn't think of it before), or that election cycles last for years at a time. The grief you feel when you leave under these circumstances is similar to how one feels when you no longer have either parent in that you lose your "center" and you know that even though you can visit, you can't go home again.