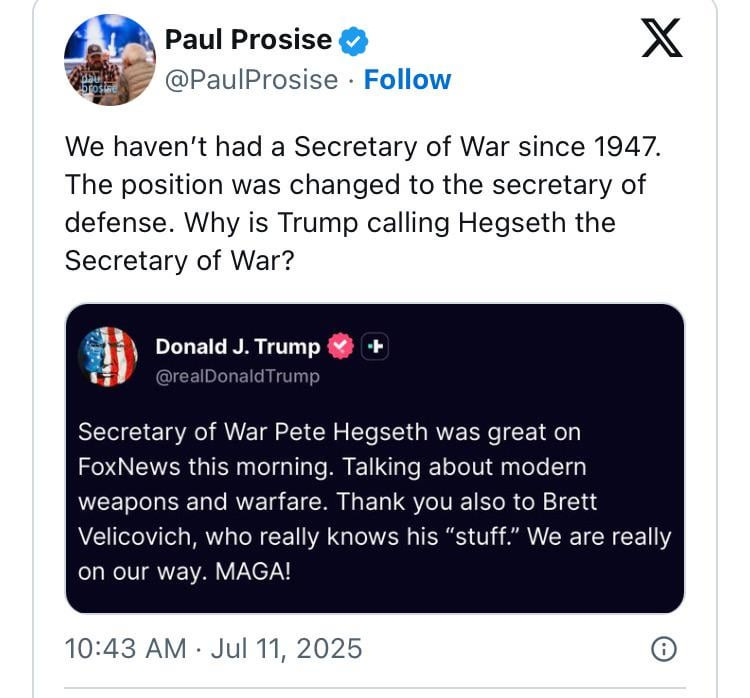

The Secretary of ... jackassery?

Yeah, it matters if it's the Secretary of War versus Defense. It matters a lot.

As with all things in the carnival sideshow of Trumpism, subtlety is dead and buried. Everything the man does has all the softness of a sledgehammer blow to the marbles without warning, and all the bravado of an Italian man of 1950.

If it isn’t strutting, preening, dick-swinging machismo, it might as well not exist. Defense? Too effete, too bookish. Secretary of War? Too quaint. What this mob of grifters really wants is a Secretary of Kicking the Shit Out of People—a title scrawled in crayon, slobbered over by their Dear Leader while Fox News hoots in the background.

And so they trot out Pete Hegseth—the human DUI checkpoint, the frat-house philosopher king of plastic patriotism—as if this bloated lackey were the second coming of Grant. In reality, he’s a cheap hood ornament on Trump’s rust-bucket jalopy of militarism: shiny enough for the yokels, but hollow tin when tapped.

Here’s the truth, and I say it as someone who’s walked the puzzle palace halls, watched the sausage of war get made, and even sat in the belly of a B-52 that still carries a hole in the ceiling for a sextant: the “Department of Defense” is not some polite euphemism, some pacifist bow-tie flourish. It is the product of generations of blood, bureaucratic warfare, and battlefield lessons burned into the nation’s skull.

America built a machine no one else has—a joint fighting force so lethal and so efficient it scares even its friends. We did not stumble into this. We clawed our way to it, out of the rubble of every botched rescue mission, every communications failure, every inter-service pissing contest that left men dead.

To go back to the “War Department” is not branding—it is brain damage. It is turning back the clock to a time when the Army and Navy could barely share a map, when “jointness” meant whose radio batteries died first.

Trump, the Mussolini of Mar-a-Lago, wants to rip up the wiring not because it will make America stronger, but because it makes for a better chant at his rallies. And Hegseth, that obedient errand boy in a shiny suit who demands everyone love him by doing pushups in the field, will happily carry the torch while the whole edifice burns down around him.

This is not patriotism.

It’s vandalism masquerading as strength.

And if we let them do it, America will not be feared, respected, or even taken seriously—it will simply be pitied, a once-mighty arsenal reduced to the punchline of a two-bit demagogue and his court jester.

A Short and Disgraceful History of the Secretary of War

The title alone told you everything you needed to know about the Republic in its gawky adolescence: Secretary of War. Not “defense,” not “security,” not “protection.” No euphemisms, no lace curtains. Just War—raw, naked, unapologetic. Exactly the sort of thing that makes Trump and Hegseth pop their buttons and squeal like hogs in a feedlot. WAR, BABY! To their kind, subtlety is for eunuchs. So let’s start here.

The United States of America, having barely staggered out of the cradle, was already appointing a man whose sole job was to decide which unlucky bastards got fed into the musket line next.

Enter, Henry Knox, our first “Secretary of War.”

Now he’s an imposing fellow, right?

Well, maybe if you’re the owner of a restaurant,

and it’s an “all you can eat” offer at the buffet.

The post was born in 1789, with the ink still wet on the Constitution, and the first officeholder, Henry Knox (yes, for whom the fort was named), looked like a man carved entirely out of pudding. From there, the job became a revolving door for hacks, halfwits, and political stooges who treated the U.S. Army less like a fighting force and more like a personal employment agency for their in-laws.

For the better part of a century, the Secretary of War was less a strategist and more a glorified quartermaster. He shoveled contracts to cronies, handed out commissions like party favors, and let the actual generals fight over maps, horses, and the privilege of bleeding out on America’s behalf.

Edwin Stanton, 27th Secretary of War, and totally rocking a pimptastic beard.

Truly a hit with all the ladies, they’d feel him coming from a mile away with that

brow tickler from halfway across the room. By the way, another massively masculine

man of machismo. Don’t you think?

I mean, wow, John Wayne looks like a pansy compared to Stanton.

In the Civil War, the job became the epicenter of graft—War Department contracts made whole fortunes for the sharpers of the age. Lincoln’s Secretary, Edwin Stanton, at least had the decency to look like a vulture, which suited the carrion he oversaw.

Bad beef purveyor and considerably more trim, bearded pimpmaster, Russell Alger. He was the 20th Governor of the State of Michigan, our 40th Secretary of War, and Michigan’s US Senator (one term) after that. Clearly, a beard maketh a man. If he had a beard as long as Stanton's, he’d have probably wound up President or Pope.

The Spanish-American War finally exposed what a joke the setup had become. Soldiers shipped to Cuba with rotten beef and malaria for dessert, while the Secretary of War, Russell Alger, treated the whole catastrophe like a Boy Scout jamboree. The public outrage was so loud that McKinley had to sack him and invent the modern scapegoat ritual.

By the time the 20th century rolled in, America’s military machine was too big, too modern, and too damn lethal to be left in the hands of a single War Secretary doling out favors like a ward boss. So they split the atom: the Army under War, the Navy off on its own, and the whole system a bureaucratic knife-fight until World War II proved the obvious—that the setup was insane.

It is a miracle bordering on divine comedy that in World War II the United States managed to fight as “cohesively” as it did. And let’s be honest: it wasn’t cohesive at all—it was a lucky brawl, a barroom melee on a planetary scale. In the Pacific, you had the Navy and its pet Marines swaggering about like pirates, blasting apart a sea-borne empire. In Europe, you had the Army and its adolescent Air Corps—later rebranded as the Air Force—slugging it out with Hitler’s legions like a pair of drunks swinging broken bottles. The two “departments” were separated not just by 14,000 miles of ocean but by philosophy, doctrine, and an unspoken hatred of each other’s guts.

Today we talk about “combined arms,” as if the machine were born perfect. In 1944 it was the high-water mark of War Department buffoonery—each service its own kingdom, each general his own god. On one side of the world, Douglas MacArthur, the peacock warlord, strutting about in corncob pipes and sunglasses, styling himself the Caesar of the Pacific. On the other, Dwight Eisenhower, the Midwestern schoolmaster, somehow persuading a gaggle of prima donnas to act like an army long enough to cross the Rhine. And in between them, a constellation of brass-hatted egotists whose chief accomplishment was proving that West Point and Annapolis could mass-produce vanity in bulk.

That we won was not proof of cohesion. It was proof of industrial might, dumb luck, and oceans full of blood to cover the cracks.

Responding to the “lessons learned” from World War II, and all that stovepiping, in 1947, the War Department was finally put down like a rabid dog, its name scraped off the letterhead and replaced with the Department of Defense. A polite euphemism, yes, but at least an honest one about what the machinery was meant to do: coordinate, integrate, and win. The Secretary of War faded into history, a relic of a cruder age—one part Roman circus master, one part ward-heeler, and one part national embarrassment.

Things weren’t hardly fixed, however. What came with the Secretary of Defense was better, but hardly “solved.”

Victory on the Potomac

The Department of War died in 1947, not out of moral enlightenment but out of sheer embarrassment. After two world wars, it was painfully obvious that America’s services could barely tolerate one another. The Army thought the Navy were dilettantes in dress whites. The Navy thought the Army were illiterate grunts who couldn’t find Europe on a map. And the Air Corps? They were teenage hot-rodders with new toys and no supervision.

So the great compromise was born: the National Security Act of 1947. Out went “War,” in came “Defense,” and the Army, Navy, and Air Force were shoved under one roof like squabbling cousins forced to share a bedroom. The Secretary of Defense was supposed to be the adult in the room. In practice, he was a weary referee watching three gangs knife each other for budget scraps.

Through Korea, Vietnam, and half the Cold War, the services fought harder with one another than they did with the enemy. Radios that couldn’t talk to each other. Logistics chains that collapsed at the first pothole. Rescue missions that turned into funerals because Navy pilots and Army Rangers couldn’t agree on which way was north. If the Soviets ever invaded, the Joint Chiefs would’ve strangled each other before they fired a shot.

The nadir came in the 1980s: the Desert One debacle in Iran, where an “all-star” joint force of Marines, Air Force, Army, and Navy managed to crash helicopters into each other in the desert like Keystone Cops with afterburners. Then Grenada in ’83, where Army Rangers and Marine battalions stormed the same island without telling each other, and had to use a commercial payphone to call for naval gunfire. The United States looked less like a superpower and more like a frat party armed with tanks.

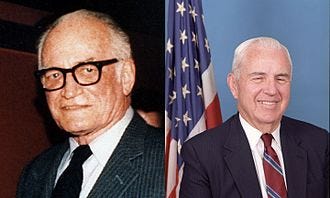

An unlikely pairing, to be sure, these two men changed our national security

(for the better) forever. Barry Goldwater, Bill Nichols, and Sam Nunn (not pictured).

Enter Goldwater–Nichols in 1986—a law that finally did what decades of “coordination” could not. It smashed the service baronies, neutered the Chiefs, and crowned the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs as the president’s main military consigliere. Operational power was handed to the Combatant Commanders—men with sprawling fiefdoms like CENTCOM and PACOM, who actually commanded forces across services. And, in a stroke of bureaucratic sadism, officers were now required to do “joint tours” if they ever wanted to make general. Nothing cures parochialism like threatening a man’s pension.

Barry Goldwater was no Caesar. He was a cranky Arizona haberdasher who stumbled into politics the way a man stumbles into a bar fight—loud, angry, and armed with nothing but his prejudices. His foreign policy instincts were equal parts cowboy and crank: nuke Hanoi, privatize the Pentagon, and yell at clouds until someone saluted. But he had one useful trait—he despised the smug little fiefdoms of the Pentagon brass. To Goldwater, watching generals squabble over budget lines was like watching a roomful of divas fight over a mirror.

Sam Nunn and Bill Nichols were no titans either. Nichols himself was a back-bencher so bland he could have been mistaken for the upholstery in his own office. He had the personality of oatmeal and the charisma of wet cardboard, but he did his homework and, unlike most of Congress, understood that jointness mattered. He was the kind of dull man who, out of sheer persistence, eventually beats people far more intelligent than himself.

Together, these men pulled off what Washington had deemed impossible: they beat the generals. Not in battle—that would have required honor—but in committee hearings, memos, and procedural chokeholds. They dragged the Joint Chiefs in front of cameras, forced them to explain why their radios couldn’t talk to each other, and made them look like prize idiots (a rare thing now, despite the surplus of cabinet officials begging for the exercise). It was bureaucratic sadism at its finest: strip the brass naked, poke them with their own failures, and make the public laugh.

The miracle of Goldwater–Nichols wasn’t genius. It was boredom and spite harnessed to lawmaking. A crank, a dullard, and a handful of staffers simply outlasted the Pentagon’s armies of lobbyists. They put into law what every soldier on the ground already knew—that the system was broken, and the only thing worse than fighting the enemy was fighting your own sister services.

And so the United States emerged, finally, with a military chain of command that worked. The Combatant Commanders became the President’s chief warfighters, the Chairman became the president’s one throat to choke, and “jointness” became a catechism every officer had to mouth if he wanted to make general.

Desert Storm was the payoff: a coordinated blitzkrieg so overwhelming that even the Russians took notes.

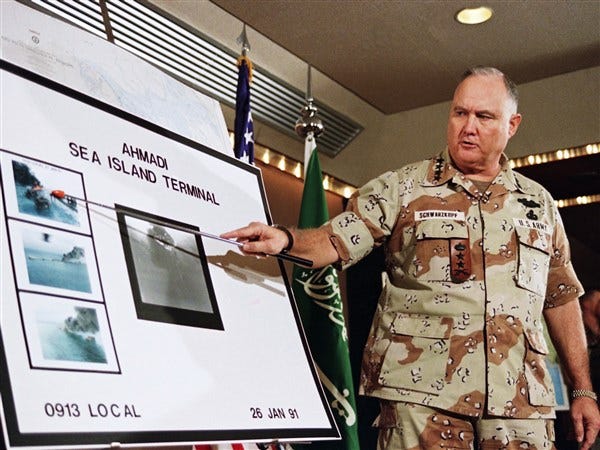

“Stormin” Norman Schwarzkopf back in 1991. Those briefings were truly

something else. It made CNN “real.” There was Stormin’ Norman, walking

us all through how our missile went left, then right, then down the chimney,

then up the Iraqi soldier’s backside. Not the one on the right, mind you, only

the soldier on the left. For those 100 hours, it was a daily infomercial to the

entire world that the United States was, in fact, the most formidable fighting

force in the history of man. It compelled one of Schwarzkopf’s subordinates,

a general in the Australian Army, to quip, “There is no combined force in

the entire world that can beat the Americans short of using nuclear weapons.”

In 1990, Desert Storm was the proof of concept—a live-fire demonstration that America’s military had finally dragged itself out of the bureaucratic Stone Age. Saddam Hussein’s army looked formidable on paper: the fourth-largest in the world, bristling with tanks, artillery, and men who’d just crawled out of a decade-long meat grinder with Iran. In the old system, the Army would have charged one way, the Air Force another, the Navy would have parked offshore looking smug, and the Marines would have shown up just to prove they existed—the result: chaos, confusion, and a body count.

Instead, thanks to Goldwater–Nichols, the United States fought as if it actually was a single military, not four competing mafias. Schwarzkopf—the Combatant Commander in charge—wasn’t begging the service chiefs for scraps. He had operational control of every Army unit, every Marine regiment, every Air Force wing, and every Navy ship in his theater.

When he snapped his fingers, steel moved. All of it. Not like Ike or MacArthur. He was our first true “theatre commander.”

The air campaign was choreographed like a sadistic ballet. Air Force bombers, Navy strike aircraft, and Marine pilots all fed into one unified plan, rather than three mutually hostile PowerPoint decks. The ground war unfolded like a set piece, with Army heavy armor executing the infamous “left hook” while Marines pinned Saddam’s forces. Communications worked. Logistics worked. For once, Americans weren’t killing each other’s plans with incompatible radios and turf wars.

The whole thing lasted 100 hours on the ground. Saddam’s vaunted army was shattered like a cheap vase. The Soviets—who’d armed and trained him—watched in horror as their client’s force was eviscerated with a precision and speed they couldn’t dream of. Desert Storm was less a war than an advertisement: this is what jointness buys you.

Goldwater–Nichols didn’t just look good in committee hearings anymore. It had given the U.S. military a functional nervous system. For once, the world’s most expensive armed forces were also the most efficient. The victory was so lopsided it created its own myth: that America had discovered a formula for effortless war. That hubris would come back to haunt us in Iraq a decade later—but in ’91, the lesson was clear. The gamble on “jointness” had paid off in spades.

Goldwater and Nichols were canonized as visionaries, but the truth is uglier and more American: the system only changed because two men who had no business running a lemonade stand managed, through sheer accident and bloody-minded persistence, to beat the most powerful bureaucracy on earth. Saints? Hardly. But in Washington, even dullards and cranks can sometimes make history—if enough helicopters crash in the desert first.

The services howled, of course. Admirals warned of tyranny, generals muttered about civilian coups, Air Force colonels threatened the death of air power itself. But within a decade, the howling stopped. By the time Desert Storm rolled across Kuwait, America finally looked like what it pretended to be: one unified military juggernaut, coordinated, lethal, terrifying. Goldwater and Nichols had done what no Soviet army ever could—forced the Pentagon to fight as a team.

It was, in the end, a victory on the Potomac. Not over foreign enemies, but over the baroque idiocies of the U.S. officer corps. And like all victories in Washington, it took dead men, public humiliation, and the gnashing of bureaucratic teeth to make it stick.

Schooling Mr. Pushups

The “DUI Hire” pretending he still runs “the squad.”

Pete Hegseth loves to flex.

He bangs out pushups or runs laps in front of the cameras on Fox & Friends like a chimp in a zoo—sweaty, loud, and desperate for attention. He mistakes this calisthenic carnival act for military wisdom, as if the real job of the Secretary of Defense were keeping count of reps. It isn’t. The Secretary of Defense is not a warlord, not a cheerleader, not a chest-thumper. The Secretary of Defense is the civilian brain of the most dangerous machine ever built.

The SecDef sits at the nexus of war and statecraft. His job is to tame the services, force coordination, and make sure that when America fights, it fights as one lethal, integrated force. He allocates budgets, balances strategy against politics, and acts as the hinge between the president and the Pentagon. In other words, he is a manager of civilization-scale violence. The office requires sobriety, cunning, and iron discipline—qualities utterly foreign to Mr. Do-Pushups-on-Camera.

And the Department itself? It is neither a gym, a parade ground, nor a set for Fox News cosplay. It is the sprawling nervous system of American power: combatant commands, logistics chains, intelligence networks, nuclear deterrence, cyber defenses, space assets, air, land, sea, and special operations—all fused into one structure that no rival on Earth has been able to match. That unity is why, since the Gulf War, the United States has remained fundamentally safe from foreign attack. The DoD has coordinated everything from storming Baghdad to patrolling the Pacific to hunting terrorists in caves, all without collapsing into the interservice food fights of the past.

Now the “DUI Hire” is a pilot! Weee! Talk to me Goose! You’re my eyes Goose!

Pete Hegseth is not a warrior. He is a cheap GI Joe knockoff, stamped out in Taiwan, sold at a truck stop, and missing half the accessories. He struts around in his Fox News blazer, the sleeves straining from pushups performed for the camera, confusing the sweat of a workout with the blood of a battlefield. His war record is a handful of staff jobs padded with the kind of self-promotion that would make P.T. Barnum blush. He talks like he’s Patton, acts like a frat boy, and has all the “situational awareness” of a mall cop on a creatine binge.

His great act of patriotism?

Not leading men into combat. Not crafting strategy. Not even understanding what the Department of Defense does.

No—his accomplishment is being a professional veteran cosplay artist, hired to grunt on command for the Fox audience, as if biceps were a substitute for brains. He is the perfect mascot for Trumpism: a man who thinks the Secretary of Defense is supposed to look tough on television.

In truth, Hegseth is the most dangerous kind of fraud: the lightweight who believes his own bullshit. He honestly thinks doing pushups and shouting about toughness makes him qualified to direct nuclear policy, global alliances, and trillion-dollar budgets. He would walk into the E-Ring of the Pentagon the way a dog walks into a symphony hall—pissing on the chairs, barking at the violins, and calling it leadership.

Hegseth doesn’t even understand what the office is for. He doesn’t want to. He just wants the title, the photo ops, and the illusion of toughness—while the machine underneath rusts and crumbles. It’s all women, liquor, and pushups to this clown. If Kubrick were making a film, I assure you, Hegseth would be in the war room, and Gen. 'Buck' Turgidson (played by George C. Scott) wouldn’t be comic relief.

Here’s reality: since the Gulf War, no peer adversary has dared to test America head-on. The Soviets folded, the Chinese bide their time, and every tin-pot dictator with dreams of glory remembers the 100-hour war that flattened Saddam. That deterrence did not come from a Secretary doing pushups on television. It came from decades of institutional reform, careful planning, and a civilian secretary who understood his job was to orchestrate—not perform—violence.

Hegseth’s fantasy of being a “Secretary of War” is the exact opposite of what America needs. He wants a mascot. The country requires a steward. He wants a stage. The job demands a chessboard. He thinks the role is about testosterone. In truth, it is about keeping testosterone-addled generals from running the country into the ground. The SecDef exists to corral the Pentagon, not to cosplay as its toughest man.

And so we revert to madness.

And now, in waltz Trump and his house jester Hegseth, babbling about resurrecting the Secretary of War as if changing the sign on the Pentagon would suddenly make America manly again. It is the politics of the locker room—men who never had the stones to fight a war trying to prove their virility by renaming the furniture.

This is not strategy.

It’s dick-measuring with letterhead.

Trump himself is the most cowardly draft dodger ever to mistake a cheeseburger for a Medal of Honor. The man couldn’t march across a golf course without a golf cart, yet he puffs out his chest and imagines himself Caesar. His idea of combat is stiffing contractors and shrieking into a microphone. He loves war the way a drunk loves fireworks: loud, bright, and only fun until someone loses a hand.

We buried the War Department and its approach because it was a failure. We clawed through decades of bureaucratic idiocy to build the Department of Defense and then hammer it into jointness under Goldwater–Nichols. We proved in Desert Storm that unity of command and integration of services was the key to modern victory. That’s the inheritance. That’s the machine. And these carnival barkers want to take a sledgehammer to it for the sake of a rally chant.

“Secretary of War” isn’t a synonym for toughness. It’s regression. It’s nostalgia cosplay for men too insecure to live in the present. It takes a century of blood, humiliation, and institutional reform and throws it away in exchange for a bumper sticker. Trump and Hegseth don’t want a stronger America—they want the illusion of strength, the kind that collapses the moment it’s tested.

To turn back the clock is not to make America mighty. It is to make it ridiculous: a superpower that mistook machismo for strategy, and bravado for victory. In short, a nation led by clowns, cheered on by rubes, and undone by its own insecurity.

This isn’t a return to strength—it’s a return to stupidity, with pushups and slogans for garnish.

Beautiful written to the point. Knowing this is

important as knowing we are not the greatest country in the world.

We only have some of the ingredients. Thanks for this.

Excellent account and analysis. Thank you.